Edna St. Vincent Millay critiques E.E. Cummings

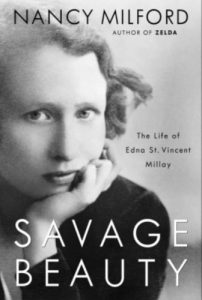

Two of our favorite poets around here are Edna St. Vincent Millay and E.E. Cummings, who, despite overlapping in lifespans, hail from two different generations of American poetry. In Savage Beauty, an excellent Millay biography by Nancy Milford, the author reconstructs Millay’s contributions to the 1933 Guggenheim Fellowship award process, in which she recommended up-and-coming poets even despite her reservations. Millay acknowledged that for her to be helping Cummings was “…really funny. For if ever I disliked a man without ever having laid eyes on him, it is this same E. E. Cummings.” This dislike was based both on his personality and some of his previously published works, though she saw promise in the latter as well:

…here is a big talent in the hands of an arrogant, peevish, self satisfied, self indulgent writer. That is to say, here is a big talent in pretty bad hands.

I am not one of those who stand for the untouchable holiness of the capital letter and traditional typography. So far as I am concerned, Mr. Cummings may do anything he likes with the alphabet, the English grammar, and the multiplication table, provided only the result of his activities be something interesting, and, after a reasonable period of application, comprehensible, to a reader of culture and brains. Mr. Cummings may not, however, I say, write poetry in English which is more difficult for me to translate than poetry written in Latin. He may, of course, write it. But if he publishes it, if he prints and offers for sale poetry which he is quite content should be, after hours of sweating concentration, inexplicable from any point of view to a person as intelligent as myself, then he does so with a motive which is frivolous from the point of view of art, and should not be helped or encouraged by any serious person or group of persons…

But, unfortunately for one’s splendid hate which had assumed almost epic proportions, by no means all of Mr. Cummings poetry is of this nature. In these books which I have just been reading there is fine writing and powerful writing (as well as some of the most pompous nonsense I ever let slip to the floor with a wide yawn), and that this author has ability I could not deny; that he has more than that I gravely suspect.

Mr. Cummings in love, for instance, his arrogance for the moment subdued, his spirit troubled and humbled, can produce such beautiful poems as are to be found in parts IV or V of “Is 5.”

If we could only trust this author to proceed along these lines, and along the line of the thrillingly lovely “Paris; this April sunset” in Part III, nothing would be clearer than that Mr. Cummings must be given anything he asks for, if it can possibly be arranged…

What I propose, then, is this: that you give Mr. Cummings enough rope. He may hang himself; or he may lasso a unicorn. In any case it is high time we found out about this man Cummings. Let us give him every opportunity to show us at once whether he is a genius, a charlatan, or a congenital defective,—and get him off our minds.

Cummings got his Guggenheim.

You must be logged in to post a comment.