A few days ago, I finally finished Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. The fact that it took me so long to read a book about typewriters, the internet, psychology, and other things I love probably proves Carr’s point better than anything I can write here. So here are some excerpts:

From chapter “The Church of Google”:

Google is neither God nor Satan, and if there shadows in the Googleplex they’re no more than the delusions of grandeur. What’s disturbing about the company’s founders is not their boyish desire to create an amazingly cool machine that will be able to outthink its creators, but the pinched conception of the human mind that gives rise to such a desire.

From “Search, Memory”:

“‘Learning how to think’ really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think,” said the novelist David Foster Wallace in a commencement address at Kenyon College in 2005. “It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience.” To give up that control is to be left with “the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.” …Wallace knew with special urgency the stakes involved in how we choose, or fail to choose, to focus our mind. We cede control over our attention at our own peril.

….In a recent essay, the playwright Richard Foreman eloquently described what’s at stake. “I come from a tradition of Western culture,” he wrote, “in which the ideal (my ideal) was the complex, dense and “cathedral-like” structure of the highly educated and articulate personality—a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West.” But now, he continued, “I see within us all (myself included) the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self—evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the “instantly available.” As we are drained of our “inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance,” Foreman concluded, we risk turning into “pancake people—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.”

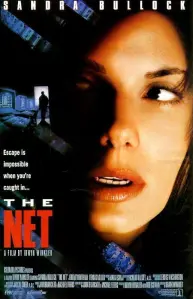

One quibble I have is that Carr consistently refers to his subject as “The Net.” Not “the internet,” as something so amorphous and omnipresent has surely ceased to be a proper noun. Not even “the Web” for a little variety. Nope, it’s always “The Net” and I always think of this:

And then I wonder how Carr neglected to mention that the internet also damages your life when your identity gets stolen in Mexico and everything hinges on copying a file to a floppy disk.

You must be logged in to post a comment.